Someone wrote on Facebook – I don’t know who, I’ve lost the post – describing Donald Trump as he walked away from the press conference at his Doral golf resort yesterday. The witness said Trump walked haltingly, his head down, his arms leaden at his sides, with his mouth hanging open. Trump had just described to the press people “who died because of the roadside bombs died and are now walking around without legs, without arms, with a face that is so badly damaged.” He claimed the war is “a little excursion because we felt we had to do that to get rid of some evil. And I think you’ll see it’s going to be a short-term excursion,” before he said that “we could call it a tremendous success right now — as we leave here, I could call it — or we could go further, and we’re going to go further.”

It was pure babble. Most of what he says is pure babble. He can keep only a couple of thoughts in his head at one time before he pivots to one of his favorite subjects, like the “rigged” election of 2020, how he “beat Biden very badly,” that Biden is the worst president “in the history of the world.”

Let me remind you tonight that we are in real trouble.

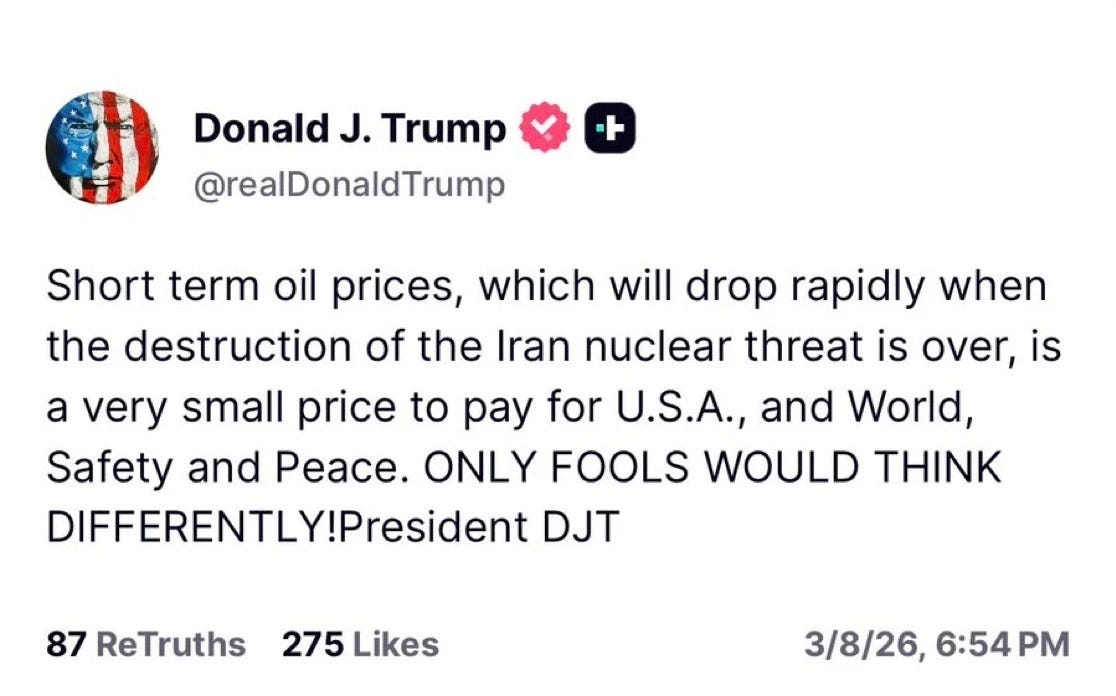

The mainstream media doesn’t behave like we are in trouble. They just sat there at Trump’s Doral press conference, and at every other press conference or Oval Office “gaggle” for that matter, and they ask him questions, and he cranks out a dozen or so lies, and they report what he says, and the entire machine of our national existence just lumbers forward. The mainstream outlets report that Trump ordered the attack on Iran because Iran was an “imminent threat to U.S. interests in the region.” Then he said Iran was an imminent threat to the United States itself. Then we are told that within a year, Iran would have had 11 nuclear weapons if Trump had not attacked with missiles and bombs and drones.

There is no proof of any of this, because proof does not matter anymore.

Trump tells us that the entire Iranian leadership has been knocked out, even the ones he liked, which is too bad, because now he doesn’t have anyone he can make one of his “deals” with, as he did in Venezuela. In fact, Venezuela starts to come up every day in the administration’s stories about the Iran attack. It begins to appear that Trump thought attacking Iran would be like attacking Venezuela.

All this is reported as if it’s just another day in America. Trump says anything he wants to say. The war is ending soon. We still have a way to go. He answers a question with a “yes.” He answers with a “no.” None of what he says means anything because nothing he says is grounded in reality. Everything that comes out of his mouth is spilling from his brain like the goo inside a Boston Cream donut that has been left out in the sun.

Information and facts and recording facts and talking and comparing facts has been with us since clay tablets were inscribed with information about trading sheep for goats and firewood for wheat in the Tigris and Euphrates Valley. We treated information seriously for thousands of years. We even turned information we discovered from the beginning of recorded time into history and declared that history is important information.

But now we have reached a point where information has no value. It doesn’t matter if something is true or false, because Trump will say whatever occurs to him at one moment, and then he will contradict what he said without acknowledging that he said the first thing, and all of it will be reported as if contradiction is normal and lies are acceptable. History doesn’t matter because history has been negated, or changed, or erased, or simply pulped. Trump has appointed one of his cabinet secretaries to the job of disassembling facts proven by science, because science doesn’t matter anymore. The Covid vaccine can kill you. It has killed “thousands” of people. The Covid vaccine has killed more people than it saved. The flu vaccine can make you sicker than the flu. Measles can be cured by taking vitamin D, or is it C? Does it matter? Thousands of children in South Carolina and Texas have not been given the measles vaccine. Hundreds are getting sick. Does that matter? Not if you believe that the cure is worse than the disease, which is what Trump’s secretary of Health and Human Services believes.

Trump has established a system in which he has no responsibility for anything. Consider this: His war on Iran is going so well, he’s playing golf on the weekend. He doesn’t have to pay attention because someone is paying attention for him. Then he picks up the phone and calls Vladimir Putin, whose intelligence services helped Iran’s military to target one of our radar stations in Saudi Arabia, and suddenly Trump is acting as if his war on Iran should come to an early end.

Did he excoriate Putin for giving Iran the intelligence that took out one of our radar facilities with equipment that takes several years to construct? Does it matter that Russia’s intelligence led to the death of one U.S. service member? Today we’re told that 140 members of our military have been wounded by Iranian missiles and drones, eight of them seriously, and Trump just talked to the man who is providing Iran with the satellite data to pinpoint where our service members are on the ground.

Does it matter that Trump betrayed our soldiers just by speaking to the man who had a hand in their deaths, and we know that he did this?

Trump is an avowed racist. He is a rapist. He has sexually abused dozens of women. He has been credibly accused of forcing a 13-year-old girl to perform fellatio on him, and when she bit his penis, he hit her on the side of her head and yelled curses at her.

Trump was best friends with Jeffrey Epstein, who we know was a pedophile who was convicted of sex trafficking a minor girl and was accused of many more sex trafficking crimes. We know that Epstein was involved in money laundering and concealing money for wealthy people in off-shore accounts. It is very likely that Jeffrey Epstein was involved in helping Russian oligarchs launder money though Trump properties. It is just as likely that Epstein helped Trump recover from his bankruptcies when no one would loan money to him.

Does it matter that we know all this about Jeffrey Epstein and Donald Trump?

We know that Donald Trump ordered the kidnapping and jailing in the United States of President Maduro of Venezuela. We know that Trump approved Maduro’s vice president taking over leadership of that country, even though her election and Maduro’s was corrupt, and another individual won. We know that the new leader of Venezuela “gave” 30 to 50 million barrels of oil, worth two billion dollars, to the United States. We know that Trump announced this “deal” and told us that he would “control” the money. We know that he subsequently sent some or all of that money to a bank in Qatar.

We know that money is not in the U.S. treasury. We do not know if “control” of the money means it is in an account belonging to Donald Trump, but that is very likely.

Does it matter that Trump ordered the U.S. military to carry out an operation to kidnap a foreign leader that resulted in his gaining access to and control of $2 billion?

All this is reported as if these are normal things that happen in the United States. Does it matter that no president has ever taken money from another country and parked it in an offshore account that he alone controls?

About Trump’s ballroom, we are told that he has “raised” $400 million to pay for a ballroom to be built where the East Wing of the White House once stood. The thing is so large, it’s like one of Trump’s skyscrapers laid on its side. Where is this money allegedly “raised” from private donors? Is it in the U.S. treasury? No, it is not, because if it was, the money would be under the control of the U.S. Congress, and that body was not even given a phone call before huge machines started to demolish the East Wing of the White House, part of a building that belongs to the United States and was paid for with taxpayer dollars allocated by a law passed by Congress.

If we are honest with ourselves, we know where that money is. It is in an account, probably in Qatar, controlled by Donald Trump, all $400 million of it.

Does it matter that one man, Donald Trump, without consulting anyone in Washington D.C. – not the National Trust, not the Congress, nobody – has decided to destroy part of the White House and build a monument to himself with his name on it?

Let’s take a moment and go back to that extraordinary day that Elon Musk was permitted to take his young son into the Oval Office and conduct what amounted to a carnival sideshow for the assembled White House press. Musk wore a black MAGA hat and danced around for nearly an hour while his son played on the carpet and picked his nose leaning on the edge of the Resolute Desk, as Donald Trump just…sat…there…with…a…blank…look…and…said… nothing.

What the fuck was that? We know Musk is the world’s richest man. We know that at that time he was running the disastrous DOGE operation that defenestrated the federal government all in the name of saving money that was never saved. We know that the government is having to rehire half the people who were fired by DOGE. We know that the whole thing was a gigantic sham, months of chaos that the government is still recovering from.

Who the hell ordered that? Did Trump allow Musk to take over the Oval Office because Musk had given him so much money, hundreds of millions of dollars, when he was running for the presidency in 2024? Why was all this treated as if it was normal, just another day in the government of the United States, another day at the White House? Why, multi-billionaires show up at the Oval Office and are allowed to run amok all the time, Lucian! Didn’t you know that?

Who has so much power over Donald Trump that he would allow such a thing to occur in his own office and by the look on his face, humiliate him no end? Who has so much power over Donald Trump that he would order the U.S. military into a war for a week and then call the leader of an enemy nation and appear to change his mind about the war he ordered?

Why are all these things being treated as if they are normal?

Does anything matter anymore?

The information we have about what is going on with our own country is valueless because there are no consequences for anything that has happened since Donald Trump took office. Trump opened his mouth at his press conference yesterday and he may as well have been screaming into a huge sucking void, for all that it mattered to the American mainstream media. Hell, we don’t even have a reasonable facsimile of a “media” at the Pentagon anymore, because Pete Hegseth fired the reporters who covered his department when they would not sign loyalty oaths. Hegseth oversaw the U.S. military going to war against Iran with no one looking over his shoulder but a bunch of right-wing podcasters that include an avowed white supremacist Nazi and several alleged “reporters” who do pretty much nothing but spread rumors about the killing of Charlie Kirk. And by the way, Trump just appointed Kirk’s widow to the Board of Governors of the Air Force Academy to carry out Kirk’s “legacy,” whatever the hell that was.

Here is the sum total of what we know about the man who is spending one billion dollars a day of our taxes on a war that we have no idea whatsoever why we’re fighting, for whom, and when it will be over, and what will happen next.

We know that Donald Trump does not get up in the morning and put on his socks and shoes and suit and shirt and tie unless he is going to get paid. We know that he has no friends. We know that he trusts no one. We know that doctors are shooting him full of some sort of drug cocktail through an IV port in one or both of his hands. We know that he spends hundreds of millions of our tax dollars so he can fly away to his own courses and play golf any time he wants to.

We know that someone is running him, but we do not know who that is, and we will still will not know even if Trump himself tells us, because we cannot believe a word he says.

We are living fully and completely in the twilight zone of Donald Trump, and we do not know when it will end, and if it does end, we do not know what happens next.