The Opinionated Ogre is a Stay-at-Home parent first, foul-mouthed hater of fascist Republicans second. He’s been making the most horrible people in the country miserable for 15 years and the hate he feels for American Nazis is eternal and without limits. He plans to stop torturing right-wing trash the day the last fascist dies. So, you know, never. Please help support this potty-mouthed newsletter for just $5/month or $50/year (Almost 17% less!)

🌊Join The Blue Wave!🌊

Prefer a one-time tip? We got you!

I’ve written a LOT of articles over the last 15 years, and I do not recall even half of them. But sometimes things happen, and a little lightbulb goes off. “Didn’t I write about this exact thing a while ago?” Usually, yes, because the American right is many things, and unoriginal ranks really high on that list. Not far below “racist,” “stupid,” and “violent.”

Here are the two things that caught my attention and set off that lightbulb.

The premise of the New York fucking Times article was simple: We’re hurting ourselves if we walk away from family and friends over something so pedestrian as politics:

Or try this thought experiment: Imagine if you had a year left to live. Would you want to spend your last Thanksgiving resenting your father’s politics? Or avoiding your sister for something she said last Christmas? Or would you rather find the grace to focus on the positives? Perhaps your father, for all his social-media-fueled hot takes, has mastered the art of carving a turkey. Your sister might be judgmental but you love her holiday-themed nails. Accepting what you can’t change doesn’t mean you’re endorsing their beliefs — it simply means doing everything you can, right now, to embrace the positives and look past the negatives.

Fuck your grace. “My goodness! You want me and my Jewish children to be gassed in a concentration camp, but just look at how neat and tidy the turkey slices are!” It offends me to even suggest such a thing. I’d rather eat my turkey with my bare hands off the floor than have it carved by a fucking fascist.

To break bread with someone who views my autistic son as a burden on society or my LGBTQ+ surrogate daughter as an abomination to be “fixed” or purged without telling the holder of said beliefs that they are a piece of shit unworthy to be in my presence IS to endorse their worldview by dint of normalizing it.

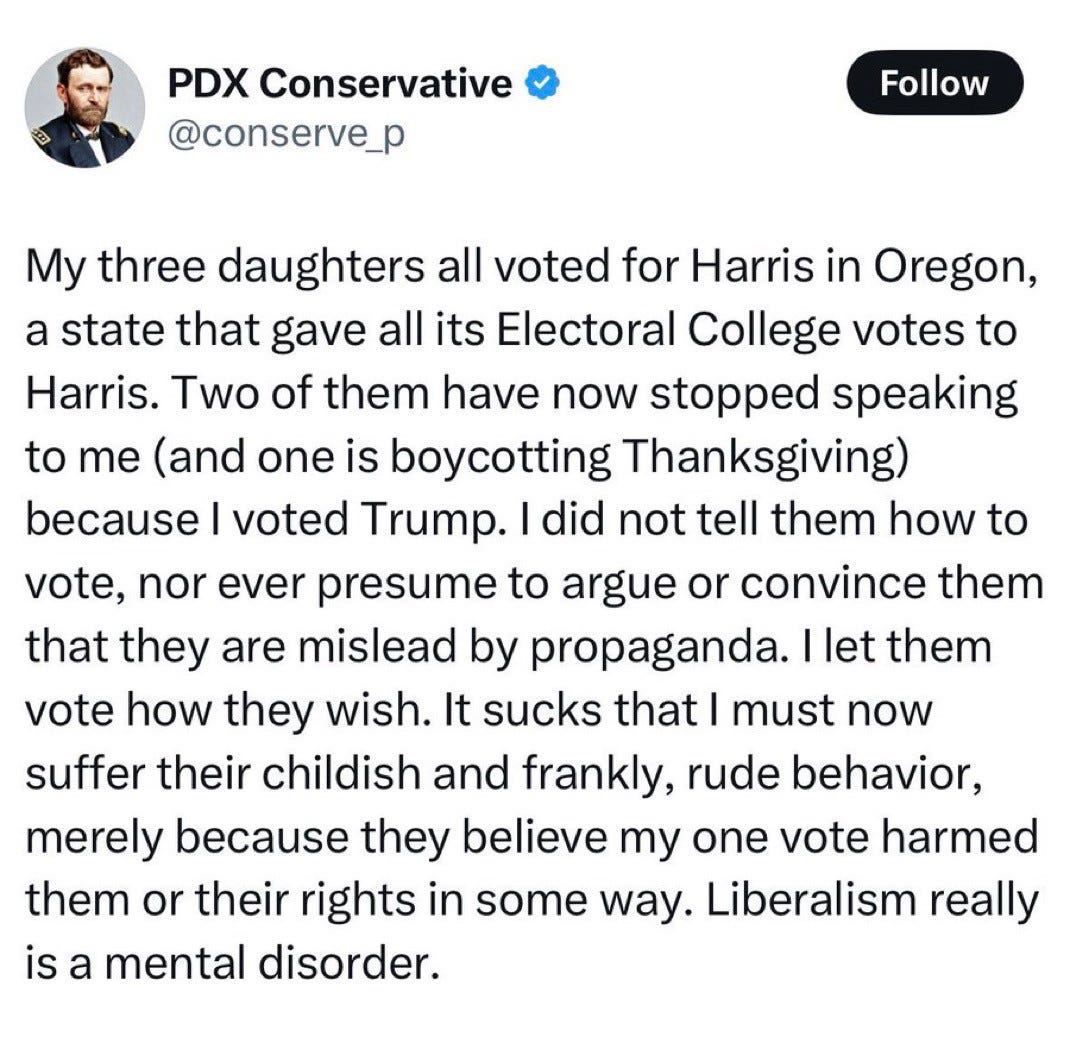

Then there was this imbecile:

It’s a mystery why this knuckledragging cockbite can’t get his daughters to speak to him anymore. He’s such a role model of parental affection and understanding!

You may or may not notice that both the Times article and Twitter post come to the same conclusion, albeit from different directions:

It’s just wrong and hurtful to cut off the Republicans in your life because of their hateful beliefs.

Now, to be clear, the Times article does not SAY which politics are causing strife or which hot takes are problematic, but it doesn’t have to. Overwhelmingly, we on the left cut off those on the right.

So much for the tolerant left!!!

To which my response is, naturally, “Go fuck yourself.” I am under no obligation to be tolerant of soulless monsters. Fuck off into the sun. But first, let me get my suntan lotion and darkest shades so I can enjoy watching you burn to ash while you do it.

Here’s the thing about the demands for tolerance: It’s part of the “both sides” lie. It’s propaganda meant to make the right look civil and decent and the left look insane and uncivil. It’s camouflage for fascists, and the press loves to help the right put it on.

Remember this pile of shit meme? I know you fucking do:

That only works if both sides have similar ideologies (life, liberty, and justice for all). Or at least similar moralities (school shootings should be prevented). That’s cute, but we all goddamn know we do not exist in the same moral universe as Republicans.

In our moral universe, we want free or, at the VERY least, inexpensive healthcare. We want equal rights for women, minorities, and the LGBTQ+ community. We want free and fair elections. We want jobs that pay a living wage. We want money out of politics. We want air, water, and food free of pollution and poison. We want to feed hungry kids.

Did you know the Opinionated Ogre has a weekly podcast? It’s true! New episodes every Thursday! Catch the latest episode here:

Join The Ogre Nation Conversation!

What do Republicans want? What do they openly SAY they want? Concentration camps and genocide. No healthcare for millions. Rigged elections. Women, minorities, and the LGBTQ+ community stripped of all of their civil rights. Not SOME of their rights. ALL of them. A country by, of, and for the billionaires, free to dump as much pollution as they want. Feed hungry kids? Fuuuuuck you! Not in MY Christian country!

They’re literally arguing, out in the open, about how many fucking Nazis should be allowed into the Republican Party. NAZIS. The people whose one overriding goal is to kill every single person who does not fit their vision of the future.

But, you know, can’t we just forgive the people who vote for them because we’re all just people underneath it all.

John Paavolitz tore into this entire concept of forgiveness and “can’t we all just get along?”:

If I have one year left to live, I’m spending it being the most authentic version of myself.

I’m not biting my tongue or avoiding difficult conversations or coddling bigots.

I’m not frittering away my final months silently abiding conspiratorial nonsense, poker-facing through an anti-gay tirade, or cheshire grinning while one of my in-laws rambles about “filthy foreigners.”

I’m not wasting my holidays keeping a tenuous peace with abject racists just because they’ve been at my table before I realized who they truly were.

I’m not squandering the last of my days playing nice with brain-rotted Fox News automatons who no longer feel empathy for anyone but themselves.

I’m not taking the chance that my last breath will be one I held, because I didn’t want to make a traitorous serial predator’s cult member comfortable simply because we used to go camping together.

And he’s being kind.

PDX Conservative, on the other hand, shows us the true face of these dipshits. His daughters are “mislead [sic] by propaganda,” you see. They’re childish and rude. They suffer from a mental disorder.

He’s the victim, y’all. Why can’t they still be family even though he explicitly voted for a pedophile rapist who spreads hate and misogyny and has directly made the country more dangerous for his own daughters? A filthy degenerate who has made the assault and rape and murder of his own flesh and blood more likely and vastly increased their chances of dying from lack of access to reproductive care?

Yes, why WOULD his daughters stop speaking to him? We may never know the answer…

So here’s the thing that’s starting to happen and holy shit are you going to start seeing soooo much more of it just like we did when I wrote about it six loooong years ago: Whenever the right is ascendant, they, and the fucking legacy press, tell us that we have to bend the knee. That they are in power, and we have to accept things the way they are. No compromising with the losers. No reaching out an olive branch. No working together for the betterment of the country. They won, we lost, fuck your feelings, libtards!

When the power shifts back to the left? When the blue wave is on the horizon after years, or in this case, just months, or Republican abuse and cruelty and corruption and violence? All of it celebrated and cheered on by Republican voters?

Suddenly, we get a steady diet of Bob and Sally memes. We get a slew of “Life Is Too Short to Fight With Your Family” articles. We get a legion of self-pitying tweets and posts from the right about how they’re the victims.

Why, I would never EVER stop talking to my child/parent/friend for voting for a Democrat! Why did they stop talking to me?! Why are they so unreasonable? Why can’t we all just get along?

But they know the answer. They’ve always known it.

When we vote for even the most wild-eyed “radical” lefty-leftist leftwinger, we are not voting to hurt anyone. We’re not even voting to make anyone feel bad. Not really. Sure, the right won’t be happy, but, you know, fuck’em. They can suffer the horrors of affordable healthcare, lower rent, safer cars, clean air, etc., etc., etc.

THAT is why the right never looks at us, on a personal level, as an imminent threat when we vote for a Democrat. They know, no matter what lies they tell themselves, that no one is going to take their guns or put them in re-education camps or rape their white women. They know we are not part of a nationwide movement to murder the white race. They know it.

But we know that when they vote for a Republican, they are voting for literal evil. They’re voting for white nationalism and children in cages and women bleeding to death in hospital parking lots and roving gangs of masked Nazis kidnapping people off the streets. They’re voting for fascism and chaos and violence and murder and genocide. And they scream for more of it. They would call ICE on their neighbor in a heartbeat. They would have their gay cousin arrested the day homosexuality is made illegal. They would give up Anne Frank and her family without a second of hesitation. We know it and so do they. They’re fucking proud of it. They rub their evil in our faces.

Until the pushback comes and it all falls apart. Then they demand understanding and civility. That’s what we’re starting to see.

Over the next year, we’re going to see a MAGAland meltdown ahead of the midterms. They’re going to alternate between “We’re unstoppable!”, because they cannot conceive of a world where they lose, and “We’re God’s most perfect victim!”, because, holy shit, every that can go wrong for the regime is going to go wrong. Even the most blind devotee is going to know the midterms are a lost cause.

After the absolute destruction of the GOP’s majority and a clean sweep across the entire country, MAGAland will look to the 2028 election and realize the next president is going to be a Democrat and their dreams of a fascist future are fucked. That’s when the real pleas for civility and understanding and “looking forward” will kick in.

It’s time for the parties to work together! It’s time for bipartisanship! All of these investigations are just corrosive to the fabric of the nation! Oh, the press will be tripping over itself, demanding the Democrats focus on “problem-solving” instead of “revenge.” They will not be able to explain why they didn’t make these same demands of the regime.

Nevertheless, the screeching for forgiveness and “moving forward” will be deafening. Because the one thing the right (and the legacy press) fears more than a future where white men do not have all the power is facing the consequences of their actions. Good luck with that, though. The American right has been getting away with this shit for over 150 years. Feels like they pushed it too far this time, and their demands for civility are going to fall on deaf ears.

Oh well! See you at the gallows, you fucking traitors.

I hope you feel better informed about the world and ready to kick fascists in the teeth to protect it. This newsletter exists because of you, so please consider becoming a supporting subscriber today for only $5 a month or just $50 a year (a 17% discount!). Thank you for everything!

🔥Burn Fascism To The Ground!🔥

Prefer a one-and-done tip? Click here!

Fascism hates organized protests. They fear the public. They fear US. Make fascists afraid again by joining Indivisible or 50501 and show them whose fucking country this is!

There are 329 days until the most important midterm election in American history. The regime is afraid, and they should be. We are legion, and they are weak. Stay strong. You are never alone.