Together with many other academics in the Netherlands, I have been very busy in organizing a nation-wide demonstration next Thursday against the 1 billion budget cuts to higher education that our very-right-wing government has announced. (For background explanation, see this earlier post).

Today, I have a long opinion piece in the daily newspaper NRC Handelsblad analyzing the crisis in higher eduction. For our non-dutch speaking colleagues, and anyone with an interest in this matter, my colleague from the law department Bald de Vries edited an AI-based translation (to which I made a few further tweaks) – you can find it below the fold.

The weaker the university, the easier it is for the cabinet to implement authoritarian policies

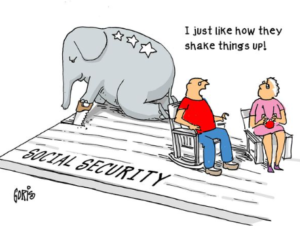

First the official line. Eppo Bruins, Minister of Education, Culture and Science (a member of NSC), has admitted to finding the cuts ‘ugly’. But the cabinet has now decided to cut higher education and science by a billion, and he has to implement it, Bruins argues.

Anyone open to rational argument must conclude that these cuts are completely irresponsible, unnecessary, and not at all legitimate.

They are irresponsible because under the previous government [Rutte III], several independent bodies found that universities were not adequately funded. An independent report by PriceWaterhouseCoopers concluded that universities were a billion euro short of performing their tasks. The Netherlands Court of Audit also issued a report in 2021 stating that universities can only perform their tasks thanks to structural unpaid overtime.

The last Rutte government, which included former Education Minister Robbert Dijkgraaf (D66), therefore proceeded to make a much-needed investment. But apparently, the current Schoof government does not find it necessary to fund universities adequately, as it decides two years later to cut another billion.

The cuts are also economically irresponsible. Every euro the government invests in university research pays for itself four times over. Some 40 companies therefore signed a wake-up call letter against the cuts. Employer association forewoman Ingrid Thijssen also argued that the cuts are not necessary at all. Better to have a budget deficit than to destroy the innovative power of the economy.

But if the government does not want a budget deficit, it would make much more sense not to proceed with the dividend tax cut for foreign shareholders, or the box 2 tax cut [this amounts to a cut on taxation on income from wealth]. Together, these tax cuts account for a billion euros in lower taxes for wealthy people, which do not serve our economy and country.

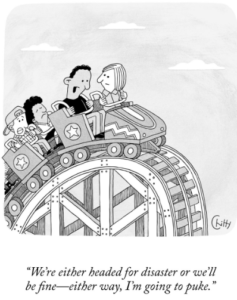

Moreover, the cuts are not lawful because they amount to a breach of contract. Minister Dijkgraaf closed a 10-year administrative agreement with the sector of higher education in 2022, which was supposed to bring calm and stability to universities. That agreement is now being unilaterally terminated by the government, without substantiation and without consultation. Calm and stability have turned into great unrest and panic, and it is only a matter of time until we will lose excellent scholars and scientists to foreign universities.

If austerity is irresponsible, economically unwise, unnecessary for public finances, and a breach of contract, then we must ask the question: what is going on here anyway? How can we understand why the government is creating this battleground?

To answer that question, we need two insights. The first insight is that one of the functions of the university has always been to keep society on its toes. The critical function of the university is crucial for truth-telling, for technological and economic progress, and for understanding society.

Universities differ from corporate R&D-departments, or from scientific think-tanks related to political parties, in that they are not supposed to serve any master other than truth, in all its dimensions. Scientists and scholars provide the facts and interpret the relevant context to societal issues. Scientists and scholars think about what questions should be asked. When they observe that untruths are being told, they should criticise it. That is the value of the university. But to act on this value, universities must be funded in a way that enables them to fulfil that role.

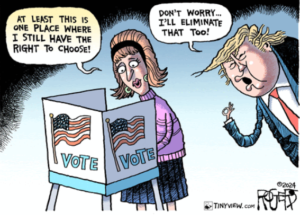

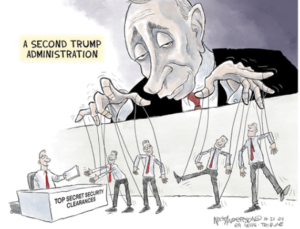

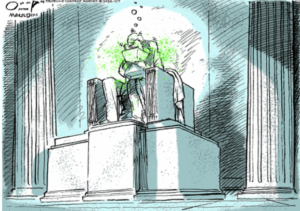

The second insight is that history teaches us time and again that democratically elected politicians with authoritarian aspirations try to undermine public institutions because they are crucial for truth-telling and the protection of liberal fundamental rights. Academia, journalism, art, culture, the civil service and the judiciary are the first to be attacked as soon as authoritarian politicians gain power. Once these institutions are sufficiently weakened, and therefore the resistance to spreading falsehoods has diminished, authoritarian parties can further strengthen their grip on society by deploying propaganda.

In the past, a lot of authoritarian politicians grabbed power from within a democratic system. The American philosopher Jason Stanley, professor at Yale University, stresses in his book How Fascism Works that we should not think that authoritarian and fascist policies only take place under a fascist regime. Even in a (weakened) democracy, a government can work on and execute fascist policies, such as dehumanising certain population groups, ignoring facts, undermining rational public debate, and spreading all kinds of myths about the nature and history of the country in order to shape the future according to its own ideal.

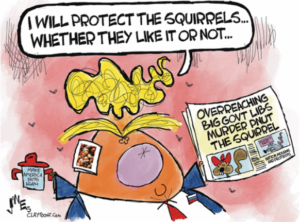

And let the university be the very place where young people are trained to look critically and constructively at society and policy, and where facts are distinguished from fiction. These are not the kind of things authoritarian leaders appreciate. For authoritarian politicians, a university is an institution that should be tamed as much as possible. Authoritarian politicians want the university to be subservient and conform to their agenda. For authoritarian politicians, anti-intellectualism is therefore part of their strategy: the weaker the position of professions that think and analyse, the easier it becomes to roll out authoritarian policies.

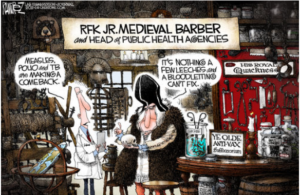

The announced cuts can easily be explainable when we recognize that the [current Dutch] Schoof government is a coalition in which anti-intellectualist parties set the tone. BBB and PVV love to create their own fact-free reality. And in doing so, scientists get in the way. Those who want to continue the current agribusiness because it yields the most short-term financial gains only find scientists’ findings on the nitrogen crisis, biodiversity loss, and climate change annoying. Nor does the PVV value social critique by scholars and scientists. Because in doing so, those scholars and scientists puncture the myths that the far-right spreads about the Netherlands’ past.

Moreover, scholars from the social sciences and the humanities sound the alarm bell about the weakening of democracy and the rule of law, and ask legal and moral questions about extreme-right policies.

For anti-intellectualist parties, it is essential that universities weaken. If they want to tighten their grip on the country, it has to be part of their long-term strategy.

What role do the other two coalition parties, VVD and NSC, play in this account? In theory, the VVD is a classical-liberal party, so it should agitate with full force against anything that erodes liberal democracy. But apparently, within the VVD, the neoliberals, who are willing to sacrifice liberal principles for tax breaks and economic policies that benefit the wealthiest part of their constituency, are pulling the strings. The question is therefore how strong the real liberals within the VVD are, and whether they will be able to protect the institutions crucial to liberal democracy from the coalition partners’ anti-intellectualist agenda.

What about NSC then? In its election manifesto, NSC promised to curb neoliberal policies, but this austerity is a neoliberal measure par excellence. And despite NSC’s emphasis on good governance, this party did appear willing to provide a minister who will unilaterally cancel the administrative agreement with higher education, without a glance. We can only hope that NSC politicians read Jason Stanley’s book and come to the conclusion that they should not want these policies on their conscience.

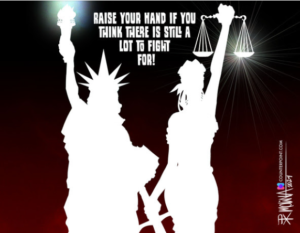

In his book On Tyranny, the American historian Timothy Snyder gave twenty recommendations on what we can do today if an authoritarian leader is elected. Lesson two is about universities, trade unions, the media, the rule of law and other institutions of free society. The lesson is: ‘Defend institutions’. This is what we should certainly expect from VVD and NSC politicians: that they conclude that their own values are being undermined with these austerity measures. And then do what is in their power to stop these cuts.

Students and scholars expect university administrators to fight the announced cuts by any morally permissible means. But in several places in the Netherlands, we see administrators who, while saying that the cuts will be disastrous, are already publicly presenting plans on how they will implement them. In doing so, they publicly accept the cuts, and hence legitimize them.

Some degree programmes had been facing financial problems for years due to the funding model, financial choices by administrators, and limited student enrollment. Deans have been working out a future-proof model for some time. But the changes now before us are of a very different order. At the University of Leiden, several programmes are being merged or scrapped, including the unique African studies programme. At Utrecht University, the undergraduate programmes in Italian, German, French, Celtic, religious studies, and Islam and Arabic are being scrapped. Even before the cuts are approved by the Lower and Upper Houses of Parliament, university administrators are already implementing them.

Our administrators should sit down with Eppo Bruins to explore what the government can do to ensure that these programmes do not disappear, instead of accepting the cuts.

Universities have become increasingly hierarchical in recent decades. In a number of faculties, professors and lecturers have virtually no say in what happens to programmes and disciplines. The thin layer of democratic varnish in university governance cannot withstand this crisis. Officially, there is co-determination, but in many places this is nothing more than a sham. It is like weakened democracy, where attempts are also being made to govern with emergency laws and without sound justification.

We need university administrators who refuse to go along with the submissiveness that the government in The Hague is trying to enforce. We need politicians who are willing to look at this issue rationally, and recognise that the planned cuts are irresponsible, unnecessary, and not legitimate. And above all, the Netherlands needs political parties that understand the bigger picture, and then decide that it is better to retract while still possible than to err completely.